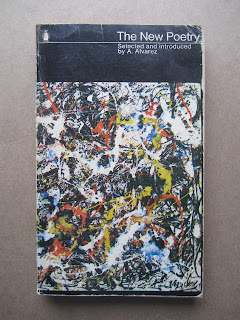

One of the first poetry anthologies I purchased was The New Poetry, a collection of British and American poems selected and introduced by A. Alvarez. First published in 1962, it was sixteen years before my sixteen-year-old self found this book at what is now one of Vancouver’s oldest bookstores to deal exclusively in new books (but, sadly, not much else).

Although

I have kept The New Poetry with me

throughout my many moves, and recognize within its Jackson Pollock cover some well-made

poems, I cannot say I was changed much by its speed and shape, nor the

sentiments its poems express. Oddly enough, the very “gentility” Alvarez despairs

in his introduction infects the poems in The

New Poetry -- a gentility of content, but also one of form.

That

said, Alvarez’s introduction serves as survey of what was going on in modern

British and American Poetry at the time -- at least what was perceived to be going if you were living in Britain (Eliot

and Pound at the old end, Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath at the new end). What is

missing, of course, is reference to Donald Allen’s The New American Poetry: 1945-1960 (1960), an anthology that was hugely

influential to a generation of Vancouver poets, largely due to the scholarship

and teaching of UBC English professor Warren Tallman, who introduced the

increasingly proprioceptive, composition-by-field poems of Denise Levertov,

Charles Olson and Jack Spicer to local student-writers like George Bowering,

Daphne Marlatt, Gladys Hindmarch and Fred Wah.

What

I like best about Alvarez’s introduction is his own poetic contribution: a poem

he composed using lines lifted from the poems in Robert Conquest’s New Lines (1956) anthology. Yet Alvarez does

not give us his “synthetic” poem to demonstrate his skills as a collagist (a

compositional method used by some of Vancouver’s intermedial artists of

the early-1960s, such as bill bissett, Judith Copithorne, Gerry Gilbert, RoyKiyooka, Michael Morris and Al Neil), but to make nonsense of what he sees as a sameness in the

poems of Kingsley Amis, Elizabeth Jennings, Thom Gunn and Philip Larkin. Leave

it to Leavis-influenced scholars like Alvarez to cheapen what was then a (re-)emergent

and refreshing literary method by employing collage not as a formal methodology

reflective of the times, but as an incongruous vehicle for connoisseurial critique.

Here

is Alvarez’s poem (and his punctuation):

Picture

of lover or friend who is not either

Like

you or me who, to sustain our pose,

Need

wine and conversation, colour and light;

In

short, a past that no one now can share,

No

matter whose your future; calm and dry,

In

sex I do not dither more than either,

Nor

should I swell to halloo the names

Of

feelings that no one needs to remember:

The

same few dismal properties, the same

Oppressive

air of justified unease

Of

our imaginations and our beds.

It seems the poet made a bad mistake.

It seems the poet made a bad mistake.

No comments:

Post a Comment